Into Darkness is the worst Star Trek film ever made.

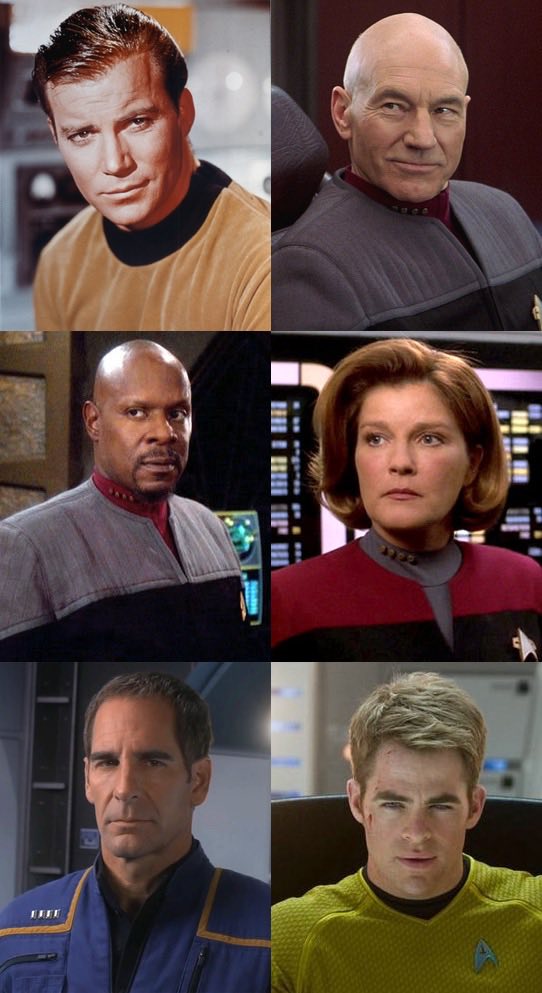

This was the verdict of the dedicated fans attending the 2013 Star Trek Convention in Las Vegas. Even the much-maligned Star Trek V: The Final Frontier, William Shatner’s 1989 directorial debut, was better received by the Trekkie crowd than JJ Abrams’ recent sequel to his 2009 reboot.

And yet, Into Darkness was a huge critical and commercial success. Brandishing an enviable 87% fresh rating on Rotten Tomatoes and generating a respectable $460 million at the global box office, the film’s broad appeal is difficult to reconcile with the vehement disdain of the enduring Star Trek fanbase.

Such striking discord makes the future of Roddenberry’s seminal science-fiction franchise - now approaching its 50th birthday - an interesting question. Paramount’s decision to relaunch Trek as a series of mainstream, action-oriented movie blockbusters did more than rile some Trekkies; it arguably disconnected the series from its central tenets.

This editorial is not a comprehensive retrospective of the Star Trek franchise. Instead, we’ll be exploring two of the most beloved moments in the Trek canon, considering what they might mean for the future of the series, and examining the themes and principles that - until recently - made the show’s various incarnations such staples of sci-fi pop culture.

With that in mind, let’s start with a brief reminder of how we got here. Our purpose, if you will; our continuing mission to explore strange new worlds, to seek out new life and new civilisations, to boldly go where no one has gone before.

Continue Reading Below...

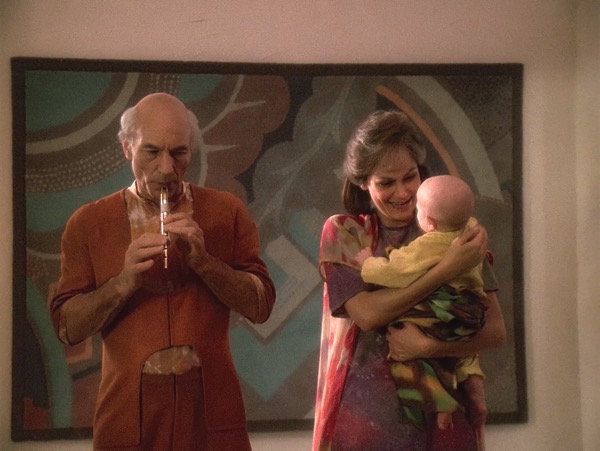

“The Inner Light genuinely explored the human condition, which this franchise does better than any other when it does it well.”

As the decades pass, the crippling drought on Kataan gets progressively worse. Kamin, now an elderly widower, watches his friends and loved ones pass away as his planet slowly dies. Finally, on the day of a long-awaited spacecraft launch, Kamin learns the truth: Kataan has been gone for millennia, destroyed by a supernova its residents were powerless to prevent. The probe was launched in a desperate attempt to preserve something of their civilisation for future generations. This interactive time-capsule contained the lifetime experiences of a single person: Kamin. The interstellar message-in-a-bottle eventually found Jean-Luc Picard.

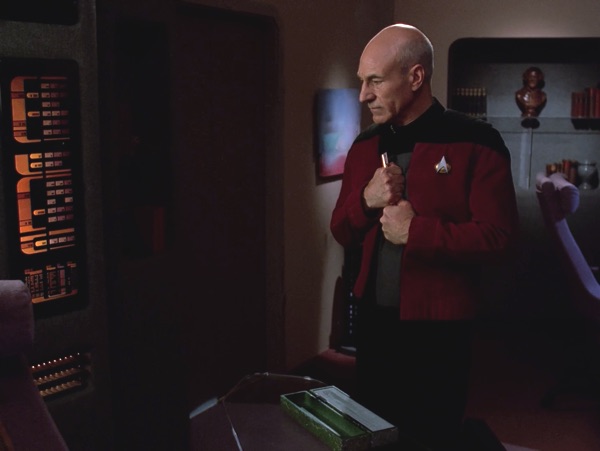

When Picard awakens on the bridge of the Enterprise, having accrued over 30 years of memories as Kamin, he struggles to comprehend that just 25 minutes have passed on the ship. Visibly shaken, he retreats to his quarters and is visited by Commander Riker bearing a gift. The probe, now disabled, contained one final keepsake for Picard: the flute that had become Kamin’s lifelong pastime. Riker departs, and Picard clutches the relic to his chest. In the episode’s wordless final scene, Kataan’s sole emissary puts the flute to his lips and begins to play.

“Now we live in you. Tell them of us, my darling.”

Taken too literally, the story of “The Inner Light” is an easy target. One might point out the implausibility of a primitive civilisation (facing its own extinction, no less) managing to beam a 30-year-long interactive life simulation directly into the brain of whichever space-faring alien happened upon their probe. Or, you might take issue with the sci-fi trope of white, English-speaking, humanoid extraterrestrials. But these criticisms are largely irrelevant to the central thrust of the episode, which is a beautiful twist on the Enterprise’s mission to seek out new life and new civilisations.

“The Inner Light” is a hauntingly significant contemplation on our own mortality, and - crucially - on the importance of storytelling to our culture. In a scene cut from the final episode, Data manages to decipher the inscription on the outside of the probe: Inside each of us lives an entire civilisation. This was inspired by a Talmudic proverb to the effect that killing a single person (and thereby his or her descendants) is like murdering an entire people. Faced with their own extinction, the people of Kataan sought to preserve their existence - not with genetic samples, as suggested by Kamin - but simply by finding someone who could walk in their shoes and tell their story.

“I always believed that I didn’t need children to complete my life. Now, I couldn’t imagine life without them.”

“It demonstrates the potential of genre fiction to astonish us and move us ... it manages to be beautiful, hopeful, and devastating all in its final scene.”

Like many of the best episodes of The Next Generation, it’s also a character study. Jean-Luc Picard, the serenely stoic starship captain, explores his personal road not taken - he falls in love, starts a family, and nurtures an introverted passion for music. Picard’s quiet life on Kataan in some ways mirrors that of his reclusive brother Robert, as seen in “Family”, the final part of the “Best of Both Worlds” trilogy. This isn’t the first time Picard has had the chance to explore the ‘what-ifs’ of his past - the omniscient super-being Q gave him a similar opportunity in the sixth season episode “Tapestry”.

However, therein lies one of the biggest flaws with “The Inner Light”, and it extends to The Next Generation as a whole. The episode is, in many ways, the epitome of the perfect science-fiction short story - it’s thoughtful and moving within its limited runtime, but largely a self-contained entity. The consequences of Picard’s experience - which would surely have been profound - are left almost-completely unexplored, a failing demonstrative of the show’s reluctance to capitalise on the serialised nature of television.

In the show’s defence, The Next Generation was never conceived of as a serial. As writer Michael Piller explained, “We try to tell stories that can be told in one hour, and that’s what we do very well.” In practise this means that the so-called ‘reset button’ is hit at the end of every episode, and the events of the preceding hour - no manner how momentous - are largely forgotten, the next episode thus starting on a clean slate.

What’s more, “The Inner Light” is actually bestowed with more in the way of follow-up than most episodes. “We were after a good hour of TV,” explained series producer Ronald D Moore. “The larger implications of how [Picard’s experience] would really screw somebody up didn’t hit home with us until later.” As such, the show’s production team contented themselves with a spiritual successor in the following season (“Lessons”). Episode writer Morgan Gendel actually published his own webcomic sequel when his idea for a follow-up episode was rejected, on the grounds that The Next Generation “didn’t do sequels”. Eagle eyed fans might also spot a few trivial references that might pass for easter eggs: the Ressikan flute makes a background appearance in a deleted scene from 2002’s Star Trek: Nemesis.

Picard’s sojourn on the long-lost world of Kataan feels like it should be the start of a much grander story. Beautifully acted and wonderfully written though they may be, episodes such as “The Inner Light” feel somehow lacking when viewed as part of a larger Trek universe.

Indeed, watch The Next Generation today and one cannot help but imagine a Star Trek with the rich, sprawling, interweaving plot-lines inherent to a heavily-serialised TV drama.

There’s just one small problem... it’s already been done.

“[Deep Space Nine] took chances in a franchise that could play it safe. We challenged the characters, the audience, and the Star Trek universe itself.”

The episode is told via flashback, and it is Sisko’s feelings of doubt and self-recrimination that drive the story. Even when Starfleet Command gives the plan their blessing (itself indicative of the Federation’s desperation) Sisko wrestles with his personal involvement in the deception, dreading the moment at which he must present Garak’s forged evidence to Romulan Senator Vreenak.

But it’s all for nothing - the Senator quickly detects Sisko’s ersatz evidence and departs the station in disgust, vowing to expose the Federation’s deception. His ship, however, is destroyed shortly after leaving Deep Space 9. Sisko, enraged, accuses Garak of using him to planting a bomb on Vreenak’s shuttle. Garak confesses that he never expected the forgery to pass inspection, and that the ultimate goal was always the murder of the Senator in Dominion space. Moreover, the damage to their evidence caused by the explosion would mask any signs of forgery, further implicating the Dominion.

Sisko is wracked with guilt, but Garak - who also murdered their sole co-conspirator to cover their tracks - argues that the captain’s actions may have saved the entire Alpha Quadrant. The Federation’s future was safeguarded, and all they had to sacrifice was the life of one Romulan senator, one criminal, and the self-respect of one Starfleet captain. “I don’t know about you,” Garak muses, “but I call that a bargain.”

“In The Pale Moonlight” is far from a perfect episode. The dialogue can be a little heavy-handed at times, with both Worf and Dax providing unnecessary commentary throughout: “A Romulan Senator has been killed? This changes everything!” Like much of 1990s Star Trek, it could also be accused of leaning a little too heavily on the crutch of technobabble, with ‘optolythic data rods‘ and ‘bio-mimetic gel‘ contrived of as plot devices.

However, the episode is also a perfect demonstration of how Deep Space Nine challenges not just viewers, but the Star Trek universe itself.

“I lied. I cheated. I bribed men to cover the crimes of other men. I am an accessory to murder. But most damning of all, I think I can live with it. And if I had to do it all over again, I would. A guilty conscience is a small price to pay for the safety of the Alpha Quadrant. So I will learn to live with it... because I can live with it. Computer – erase that entire personal log.”

In contrast to the darkness of much of today’s science-fiction, Gene Roddenberry’s vision of the future was built on the vision of a better tomorrow. With poverty, disease, war, and prejudice all but eradicated in the 24th century, humanity could aspire to greater things. As Picard rather pompously puts it in Star Trek: First Contact, “the acquisition of wealth is no longer the driving force in our lives… we work to better ourselves, and the rest of humanity.”

These utopian leanings are undoubtedly part of the series’ enduring appeal. John De Lancie, who played ‘Q’ in The Next Generation observed that “Star Trek is about something… people actually have a sense it might presage a better future.” Deep Space Nine, whilst not rejecting Roddenberry’s vision outright, tested it to its limits.

People who come from different places - no matter how honourable or principled - will inevitably have conflicts. And when put under pressure, they will sometimes make bad decisions. These truths are inherent to the human condition, and to claim that Roddenberry’s perfect vision could survive the horrors of war unscathed is hopelessly naive. Deep Space Nine takes a far more nuanced view, and explores the idea that even the most moral person will sometimes forsake their principles for a perceived greater good. For Captain Benjamin Sisko, this meant dancing with the devil in the pale moonlight.

“They call it the golden age of television [...] and it’s where all the most interesting characters have gone.”

Empowered by the serialised nature of television, those long, sweeping story arcs championed by Deep Space Nine in the 1990s are being taken to extremes. “TV is where a writer can write their novel,” argues screenwriter Richard LaGravenese. “You can have ambiguity in television that you are not allowed in film. You can have episodes that are purely character-driven, that are just about nuances and shades of the human condition.”

This is where Star Trek should be.

Our hypothetical TV reboot would have to strike a delicate balance between old and new. It should embrace the franchise’s rich heritage, certainly; it should emphasise science-fiction over science-fantasy, and bring back exploration as the central premise. The thoughtful, character-driven storytelling that typifies the best Star Trek episodes (a la “The Inner Light”) could be honoured by commissioning acclaimed science-fiction authors like Neil Gaimen and George R. R. Martin to write individual episodes. This is hardly a far-fetched idea; The Wire was famously penned by a number of award-winning crime-fiction writers.

But it must also break with the past. In his editorial, Dickerson argues that this means saying goodbye to the Enterprise, which has been exhausted as a setting. With literally hundreds of hours of Trek set aboard the ship, continued reliance on the Enterprise (and recasting of its old crews) is simply lazy. Just as Deep Space Nine scrutinised established Trek conventions - “In The Pale Moonlight” being a prime example - our new show must boldly go where no Trek has gone before.

“Just as the original series broke from convention to tell adult stories, Star Trek needs to once again break from the past and stop being about the Enterprise and crew. [...] We need to look at a new ship, a new crew, and explore new ground. Star Trek needs to move forward.”

The Star Trek franchise - with its rich mythos and entrenched norms - has become overly derivative. Indeed, those Trek shows we haven’t covered today are a particularly good demonstration of this. For all their countless merits, Voyager was basically a twist on The Next Generation (itself a twist on the original 60s Star Trek), and Enterprise - once hugely promising - was often hobbled by studio pressure to stick to the established formula.

Let’s go somewhere new. A smartly written, character-driven TV serial, set in an unexplored region - or time - of the beloved Trek universe, paying tribute to the best elements of The Next Generation and Deep Space Nine. Truly, this would represent the best of both worlds.

Make it so.

Share

Credits

Written and designed by Tom Bennet, and published in November 2014. Section header images are courtesy of The Light Works Digital Imagery, with the exception of ‘These Are The Voyages’, which appears courtesy of foundation3d.com. Unless otherwise indicated, all other images, videos, and quotes are courtesy of CBS / Paramount.

Custom long-form responsive design, utilizing Knight Lab’s TimelineJS, Jan Paepke’s ScrollMagic Javascript library, and the Greensock Animation Platform. Special thanks to all contributors to these projects.