Welcome Back, Commander.

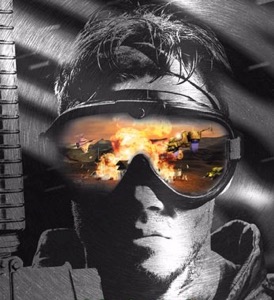

The original Command & Conquer will this year celebrate the 20th anniversary of its release.

In the intervening years, the game has spawned a franchise totalling 17 titles spanning three ‘universes’, and given birth to an entire genre of video games. With the title’s original DOS release in 1995, developer Westwood Studios single-handedly conquered the burgeoning real-time strategy (RTS) market that it had pioneered three years earlier with Dune II, and introduced the world to the concept of networked multiplayer gaming.

In its early years, at least, one could argue that the series lived up to the promise of its name. But if the history of empires tells us anything, it’s that the reign of even the mightiest of conquerers is prone to collapse. Given the dismal critical reception of 2010’s Command & Conquer 4, and the subsequent cancellation of a free-to-play reboot by a new studio, the future of the series has been called into question.

In light of these troubled times, it seems befitting to take our lead from the heroes and villains of the Red Alert saga, who - when faced with imminent defeat - would invariably jump into their time machines and try to remedy the root causes of their troubles. Alas, we cannot change the past, but with fresh insight from ex-Westwood developers Frank Klepacki, Eric Gooch, and Joe Bostic, we can revisit the series’ genesis twenty years ago.

Here, we’ll explore the humble beginnings of the Command & Conquer franchise, and shed light on the development of its first two seminal titles. This is the tale of Tiberian Origins.

The Land of Nod

The original Command & Conquer, a sci-fi classic affectionately dubbed Tiberian Dawn by fans, actually began life as a fantasy game complete with wizards and warriors. Following on from the remarkable success of Dune II, Westwood Studios sought to refine their popular RTS formula with Command & Conjure, a high-fantasy strategy epic which began development in early 1993.

The move over to a more realistic setting came at the behest of Westwood co-founder Brett Sperry, who felt strongly that the political climate of the mid–1990s - particularly the First Gulf War - would make a modern setting more accessible. “At the time,” explains fellow co-founder Louis Castle to CVG, “[Brett] felt that the next wars wouldn’t be fought nation-to-nation, but fought between Western society and a kind of anarchistic terror organisation without a centralised government.” This remarkably prescient view led to the birth of C&C’s now-famous parallel universe.

Populating this new fictional world proved more challenging than simply licensing an existing property, as the team had done with Dune II. The writers invented a supranational organisation called the Global Defence Initiative (GDI), and pitted them against the Brotherhood of Nod, a cultish militant society spread throughout the world.

“It was the Wild West during those early days of the games industry. People working on a game would fulfil overlapping roles. I did much of the tactical gameplay design work and even a little bit of art.”

At the centre of the struggle was Tiberium, a crystalline substance of alien origin slowly propagating itself across the planet. Having arrived on Earth via a meteorite several years earlier, the toxic (and highly valuable) material is believed by Nod’s followers to hold the key to the next stage of human evolution. “Much of the backstory came from the creative imagination of Brett Sperry and Eydie Laramore,” explains Joe Bostic, lead programmer at Westwood. “The B-movie Monolith Monsters was also an inspiration – watch it, and you’ll see strong parallels to Tiberium.”

Detailed backstories were created to flesh out the game’s universe, and were recorded in a binder for reference. Maintained by Eydie Laramore, the volume expanded to accommodate the rich histories created for Kane, the Brotherhood of Nod, and Tiberium. “We called it the C&C Bible,” recalls Bostic. “It was many inches thick, and served as the source material for many of the stories in the subsequent games and expansion packs.”

“It was very indie. We had a small green screen and a handful of props and costumes, and only room enough to film one person at a time!”

Perhaps the most memorable aspect of the game’s story is the manner in which it is told. Riding the wave of the CD-ROM revolution, the developers made the unusual decision to take advantage of full motion video (FMV) for the cutscenes. With a limited budget and no proper studio in which to film, most scenes were shot on-site with Westwood’s own staff doing the acting.

“When we first started out, we were flying by the seat of our pants,” recalls Eric Gooch, a lead 3D artist at Westwood. “There was no stage or studio. We had an upper floor in a warehouse a block away that was used for storage. I bought a roll of linoleum, and stapled it to the wall as a background, curved the base of it to act as a cyclorama, and painted it green. That was our first greenscreen!”

Such were the technical constraints facing the team, many of the more-complex shots entailed tricks in post-production. The greenscreen was only large enough for one person to be filmed at a time; whilst sufficient for close-ups and mission briefings, it did not allow for wider shots to be filmed naturally. Frank Klepacki, Westwood’s sound designer and composer, recalls the manner in which the final Nod cutscene was shot: “For the cyber attack sequence, the three of us took turns sitting in the same chair shot at 3 different angles, pretending to navigate through the Orbital Defence System. Then I was told to act like I got electrocuted!”

The single professional actor involved with the production was Joe Kucan, originally hired to direct the filming but chosen soon afterwards to play Kane, Nod’s enigmatic leader and self-proclaimed messiah. Joe, however, was not the only person to find themselves in an unexpected acting role; Eric Gooch, responsible for lighting the FMV sequences, recalls the circumstances under which he was cast as Seth:

Joe: “And that’s when Seth tells the player that he... oh crap.”

Eric: “What?”

Joe: “We forgot to cast Seth.”

Eric: “Ha!”

Joe: “You could be Seth! Do you want to be Seth?”

Me: “Sure!”

As development progressed, the team collectively sensed that they had something very special on their hands. “You can never know if you have a hit or an instant classic,” observes Klepacki, “but you can know that you have something special - and the original C&C certainly had that magic to it.” Playtesters had a propensity to get carried away and start playing for fun, and the game’s addictive nature and remarkable popularity at trade shows drove the Westwood team to a new level of enthusiasm for Command & Conquer.

“The atmosphere was good. There was a lot of experimentation, because we were starting to use 3D for the first time. Up until then, on games like Kyrandia and Lands of Lore, everything was pixels and paint programs. So it was pretty exciting to figure 3D out.”

Ultimately, it proved to be the game’s LAN multiplayer feature that really caught the public’s imagination and sealed its success. Westwood had the foresight to release the game on two discs, one for each faction, which allowed competitive matches to be fought using a single copy. This was advertised prominently on the retail packaging, which included the slogan, A second copy, so you and your friend can destroy each other!

“The multiplayer was key to C&C,” says Bostic. “You could play multiplayer with either the Nod or GDI CD in your PC, and because [the game] could be played over direct LAN cabling, it meant that LAN parties sprang up to play C&C.” Indeed, for its time the game boasted a remarkably deep set strategic possibilities. Mastery required players to match the strengths of their chosen faction against the characteristics of their opponent (GDI’s strong but slow-moving units versus Nod’s stealth and speed). It was a formula that rewarded regular competitive play, and that the franchise’s developers would broaden and refine for decades to come.

“I was encouraged to try different styles, from metal to rock to hip-hop, to make the soundtrack diverse. That was part of the joy of working on it for me.”

Upon release, the game’s impact was phenomenal, both critically and commercially. Such was the demand for additional content, the team wasted no time in producing an expansion pack, entitled The Covert Operations. Released early the following year in 1996, it contained 15 notoriously difficult single-player missions and 10 new multiplayer maps. The immediate fan demand for more C&C satiated, Westwood turned its attention to creating a true follow-up. However, the seeds for this new game - provisionally titled C&C 0 - had already been sown.

Frank Klepacki remembers the manner of his first contribution to the sequel. Whilst experimenting with a metal song intended to be a theme for the Brotherhood of Nod, Brett Sperry visited Klepacki’s office.

“What’s the name of this one?”, asked Sperry upon hearing an early demo of the track, which featured synthesisers and heavy guitar riffs over voice samples of a marching drill.

“Hell March,” said Klepacki.

“That’s the signature song for our next game,” replied Sperry.

C & C Zero

The connections between Command & Conquer’s Tiberium saga and the Red Alert spin-off games are oft-debated amongst fans of the series. Subsequent instalments may have clouded the waters, but at the time of its inception, Red Alert’s purpose in the eyes of Westwood’s developers was clear.

“It soon became apparent that a straight WW2 fiction was too limiting, so we needed to add a twist. That is where the alternate history time travel aspect came into play. It allowed us to be as true to WW2 or be completely wild in whatever degree we wanted.”

“While we were doing the military research for C&C we’d come across all these crazy ideas,” recalls Louis Castle to CVG. “The Philadelphia Experiment, […] time travel, teleportation, and so on.” Inspired by stories of bizarre science experiments during the Cold War era, the team became interested in exploring an ‘alternate history’ of World War II, pitting Soviet Russia against the Western allies. As the concept developed, the team quickly realised that such a scenario would be a perfect opportunity to explore the origins of the universe established in Command & Conquer.

Originally intended as an expansion pack for the original, Red Alert’s alternate history setting proved so liberating from a creative standpoint that the decision was made to launch the game as a standalone title. Whilst it allowed the team to explore the myriad of exciting opportunities for story and strategy afforded by the new setting, this change of plan did not alter the production timeline. “We were still under the schedule for an expansion pack, so we had to finish the game in 9 months,” laughs Joe Bostic. ”Even though small teams are fast, that was a pretty intense 9 months!”

The game’s story - once again told using FMV sequences, albeit filmed on a slightly larger greenscreen - is set in motion when Einstein travels backwards in time to remove Hitler (and thus the Nazis) from history. In this new timeline, the Cold War escalates into another World War between the Allies - who form the precursor to GDI - and the USSR, the government of which has been infiltrated by Nod. Whilst later games in the Red Alert series embraced a cheesy sense of humour, this first entry was remarkably straight-faced.

According to Adam Isgreen, a lead designer on many of Westwood’s Command & Conquer games, early drafts of Red Alert’s script featured a ‘duelling scientists’ sub-plot, the increasingly bizarre inventions of Albert Einstein and Nikola Tesla fuelling a technological arms race. Many elements of this idea are present in the finished game, including teleportation with Einstein’s Chronosphere, weaponised Tesla coils, and a defensive force field dubbed the ‘iron curtain’. Fascinatingly, this facet of the story was also intended to provide further connections to the original game - Tesla, who famously speculated about radio communication with extraterrestrials, would have successfully contacted an alien civilisation during the arms race, an event leading to the eventual seeding of Tiberium on Earth.

“A remarkable thing about the game’s development was the rapid iteration process. We would play C&C in the evening, make lots of code and design changes the next day, and then play the new version that evening to repeat the process.”

On a more mechanical front, Red Alert took many of its predecessor’s innovations to new heights. Its diverse range of single player missions included convoy escort, assassination, hostage rescue, espionage, as well as the grand, full-frontal assaults for which the franchise had become known. But the quality that made Westwood’s prequel truly shine (and, indeed, that would later carry its 2000 sequel Red Alert 2 into the realms of RTS legend) was the depth of strategy afforded by its strikingly different factions. This was the result of a concerted effort by the Westwood team, supplemented by extensive playtesting.

“Red Alert was the first game where we tried very hard to make the sides as different as possible. Balancing […] was very difficult to do.”

Development of Red Alert proved to be just as enjoyable as that of the original. “Playtesting was great fun,” recalls Joe Bostic. “We could react so fast that were often able to turn around a new feature in a single day to see the effects.” The game proved extremely popular amongst Westwood’s own staff, and was so addictive that playtesters tasked with identifing bugs would often abandon the job in favour of pursuing a decisive victory. “Testing helped us learn strategies that we would add to the AI,” says Bostic, “but the game was so enjoyable that testers would often get wrapped up in trying to win rather than trying to get a particular bug to repeat!”

The tremendous success of the original game did not instil a huge change in the team’s workflow, as one might expect. “For both Command & Conquer and Red Alert, there was a strong visual theme right from the start,” recalls Eric Gooch, describing how the team created the now-famous alternate history versions of the Allies and Soviets. “Once we got the concepts, we’d start creating the models, then refine as we went. Weekly art meetings were held, with the team commenting and critiquing work as it was created.”

The atmosphere at the studio, too, remained unchanged. “Everyone contributed in multiple ways and game development iteration was very quick,” says Bostic, recalling the creative freedom afforded by the company structure. Echoing a sentiment heard from many Westwood veterns, he describes the atmosphere that typefied the studio, and which would later be lost during the ill-fated EA aquisition deal. “It is a tribute to the low overhead (few managers) and small team size that characterized Westwood in those days.”

“There was very little specialisation. A cinematic artist would be handed a storyboard, and told to ‘make this into a movie.’ We would then model, texture, animate, light, do our FX work and compositing.”

Like its predecessor, Red Alert was a huge success for Westwood. Upon its release in 1996 the game was met with universal critical acclaim, with reviewers praising everything from its soundtrack to its startlingly addictive multiplayer mode. GameSpot’s review is a good reflection of the gaming community’s collective assessment of Westwood’s new title. It declared Red Alert to belong “in the same category as Civilisation II and Quake II”, games that followed legendary predecessors and immediately eclipsed them. “One can only wonder where Westwood can take us from here,” concluded the reviewer.

For some members of the team, the runaway success of Command & Conquer had seemed almost surreal; only when Red Alert offered proof that lightning could, in fact, strike twice did the realisation truly hit home. For composer Frank Klepacki, that moment came with the reception of the sequel’s soundtrack.

Not only was the album named soundtrack of the year by PC Gamer, but game’s main anthem - his first contribution to the sequel - was quickly becoming a classic. “Hell March reached iconic status with the fans, and that just blew my mind - that’s when it really registered with me that we had achieved something awesome, more than just a game or die-hard appreciation,” remembers Frank. “We’d made something that people love.”

Directives Reassessed

By the time Red Alert shipped on Halloween of 1996, Westwood had laid the foundations for what would become one of gaming’s most beloved and influential franchises. The Command & Conquer brand would even survive the tragic closure of Westwood in 2003, the result of an acquisition which Electronic Arts (EA) has openly admitted to botching. Nevertheless, the fate of the well-loved development studio (and of the C&C franchise) continues to fuel bitterness within the community to this day.

“The creativity of the development team that was allowed to thrive is a testament to how the project and the studio were run. Great and exciting times.”

But that’s a story for another time. The dozen titles that followed the two we’ve explored today, along with those that were cancelled - chiefly Renegade 2, Continuum, and Tiberium Incursion - are each worthy of their own retrospectives. Readers who are interested in exploring these lost C&C games should head over to CNCNZ. The future of the franchise, too, is a fascinating topic that we will not be exploring here. (Although all C&C fans would do well to check out Sonic’s excellent editorial pondering this very question.)

There is but one final question that any consideration of C&C’s origins would be incomplete without, and that is of the availability of these older games.

As a videogame platform, the PC is better positioned than most when it comes to the preservation of its classics. Unlike console games - which typically rely on proprietary hardware and a rigid operating system - PC games are necessarily built for a more open platform. With services such as GOG (formally ‘Good Old Games’) offering low-cost, DRM-free editions of classic games, patched and restored for modern operating systems, select publishers are preserving their catalogues for future generations to enjoy.

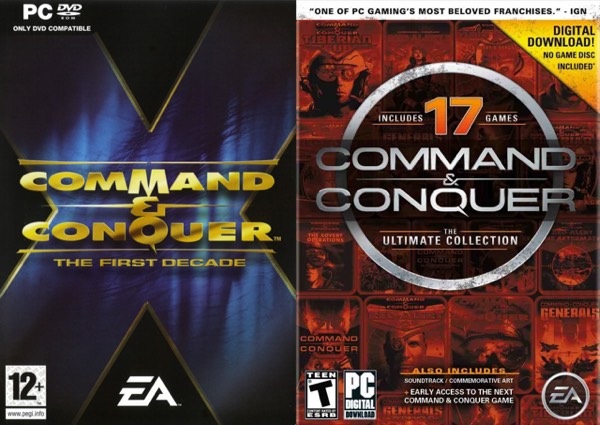

The C&C franchise has been repackaged several times by EA, with both 2006’s The First Decade and 2012’s The Ultimate Collection containing all the games available at the time of their respective releases. However, in neither of these collections were the older games updated to run properly on modern operating systems, the gargantuan support threads on EA’s forums contradicting the company’s declarations to the contrary. The latter release, which relies on EA’s Origin platform, is buggy and prone to crashes, its online matchmaking services have been completely retired, multiplayer over LAN is nigh-on impossible for the older titles, and fan-made patches are often the only way to get the games running at all.

Ironically, this is less of a problem for the very oldest titles in the series, which EA released as freeware several years ago. This was arguably more of a tokenistic gesture than a genuine attempt at preservation - Disney’s marvellous handling of LucasArts’s treasure trove of a back catalogue has set expectations high indeed - but at the very least, it passed responsibility for the future of these games over to the community. The old retail disk images for Command & Conquer, the first Red Alert, and Tiberian Sun are thus available for free online, and can be found with minimal effort.

What’s more, the fans have done a truly stellar job where EA has fallen short. Owners of The First Decade compilation can repair all their games in one fell swoop thanks to an unofficial fan-made patch hosted at CNCNZ. Those wishing to replay the original C&C can download the full game, free and fully-patched, thanks to the work of Maarten Meuris. And for gamers keen to revisit the first Red Alert (or, indeed, to play any of the classic C&C titles online) CnCNet has you covered. Their fantastic installers are also available in Wineskins for gamers on OS X & Linux.

The wider C&C community is doing similarly remarkable things. 2014 saw the release of Renegade X, a fan-made Unreal-powered remake of Westwood’s FPS, as well as the continued development of OpenRA, an open-source recreation of the classic C&C titles that supports cross-platform multiplayer. Finally, there was the launch of C&C Online, a fan-made multiplayer server, without which the competitive communities for Generals, Zero Hour, C&C 3, Kane’s Wrath, and Red Alert 3 would now be dead and buried.

With 2015 marking the 20th anniversary of Command & Conquer’s release - and, as it happens, the would-be 30th birthday of Westwood Studios - now is the perfect time to revisit the origins of RTS. There’s no shortage of classics to choose from.

In the words of Nod’s leader: “The choice, my friend, is yours...”